By Ali Follman

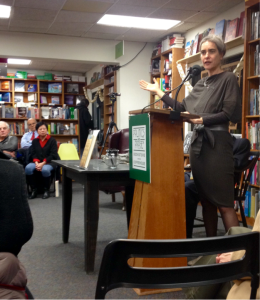

Above: Author Sarah Chayes speaking at Politics and Prose bookstore on Jan. 21 in Washington, D.C. Photo by Ali Follman.

During her 10 years of reporting and fighting against public corruption in Afghanistan, Sarah Chayes has seen the CIA hand tinfoil-wrapped bundles of cash to former President Hamid Karzi.

The reason for this exchange and other interactions between the United States and Afghanistan governments is unknown. While Chayes served as a former adviser to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Afghanistan in the late 1990s, she saw first hand corruption in the government directly affecting other nations, including the U.S. “We are buying the bullets that are killing our soldiers,” Chayes said.

The former international NPR correspondent, Peace Corps alum, expert in anticorruption and American-turned-Afghan resident promoted her new book, Thieves of State: Why Corruption Threatens Global Security at Politics and Prose in Washington, D.C. on Jan. 21.

From her work inside the Afghan government with former President Karzai, she learned the ways his organization takes aid money and funnels it elsewhere. Afghanistan was not in a solid state, she said, as some Afghans went back to the Taliban. This is why the country turned to the U.S.

With a degree in Islamic history from Harvard, Chayes, 52, spent 10 years in Afghanistan covering the Taliban for NPR. After that she left journalism to focus on reconstructing the country starting with the government, according to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, which she works for now as senior associate in the Democracy and Rule of Law Program and the South Asia Program.

“At some point, there weren’t any Americans who had been out there [in Afghanistan] that long,” Chayes said. She described adjusting to life in Afghanistan by wearing a turban, pretending to be a man in some cases, and blending into the culture to write stories to send home.

The problems Afghanistan faced in the early 2000s rooted in its government. The country couldn’t move forward because of its leaders. She told stories of so-called “governors” in Afghanistan who vanished with piles of cash that were meant to be put back into projects she was working on directly. “Money has overwhelmed every other social value,” Chayes said. “Money is being extracted upwards.”

With no panacea, Chayes is currently working on the link between the rise of military extremism and acute public corruption with the Carnegie Endowment.

Prompted by a question from the audience, Chayes said opium is a huge part of the Afghan economy. She participates in antinarcotics talks overseas and helps Afghans explore alternatives to the opium trade in their economy. “International assistance is a revenue stream…down to the opium trade,” Chayes said. In a report by the Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction in fall 2014, it confirmed that the U.S. military forces in Afghanistan had no primary plan to defeat corruption fueled by the illegal drug trade.

Chayes said Afghanistan had a good, functioning government in the 1960s. But the United States military presence later on may have aggravated the system. Around the 1990s, the Afghan government was often dismissed as weak or failing, she writes in her book, but it was actually an organized operation of crime instead of one that offers social services. “[The U.S.] Installed a government of thieves above us [the Afghan people],” Chayes said. Chayes was so involved with helping Afghanistan that she felt she was a citizen and not just an anti-corruption expert.

The people of Afghanistan looked to the U.S. for a government by law and not by religion, she said. “You can’t talk to someone about corruption when they’re the one corrupting,” Chayes said. Religion, the deification of money, and the “tribalist” reputation of the Afghan people all add to the issue.

In President Obama’s speeches, Chayes said he has stated many times that there isn’t a military solution to end this corruption, and that he offers more solutions using the military instead of solutions using governance. “There isn’t a military solution so you have to work on the non-military solutions,” Chayes said.

The audience asked who could specifically help this type of government. Her answer: Peace Corps members, journalists, financial experts, people who are educated, have negotiation skills and are good at interacting with others who are different from themselves are all necessary to fix a government.

“We brought an elective dictatorship to Afghanistan,” Chayes said. As part of Chayes’ work in Afghanistan, she made a list of corrupt leaders, some she has worked with, who should be replaced because of their corruption. She sent these recommendations to the U.S. government to consider, but her work to end corruption she said will never end.